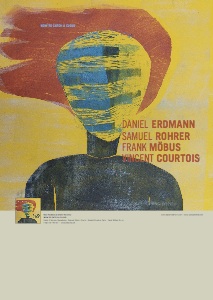

Daniel Erdmann & Samuel Rohrer 4tet

"how to catch a cloud"

Daniel Erdmann - tenor saxophone

Vincent Courtois - cello

Frank Möbus - guitar

Samuel Rohrer - drums

MUSIC THAT HINTS

Daniel Erdmann – Samuel Rohrer – Vincent Courtois and Frank Möbus and their jazz of restraint.

For most of its history, jazz was a soloist’s music: one melody instrument improvising (saxophone, clarinet, trumpet or trombone), accompanied by a rhythm section. The composition’s theme was generally just a departure point for the soloists’ excursions. What counted most was the solo – that was where musicians could show off their virtu- osity and aplomb, that’s where they displayed individuality and fantasy, as well as a deeper understanding of the harmonic subtleties of jazz. The fact that the audience applauded every solo (within the music and over the theme) told you how differently these two elements were valued.

In the fifties this principle was shredded. Bandleaders like Charles Mingus or Chico Hamilton led their ensembles through ever more complex compositions, while arrangers such as Gil Evans and George Russell enhanced the value of accompaniment as against solos.

One decade later free jazz overthrew the hierarchic order of soloist and accompanist, freeing the rhythm section from their servant’s role. Bass and drums were set on a par with melody instruments. In this new democratic jazz everyone played solo. “Nobody solos, everybody solos,” was Joe Zawinul’s famous adage from the early days of Weather Report, as they laid the foundations for jazz-rock.

Daniel Erdmann and Samuel Rohrer stir fresh ingredients into this musical stew. Their jazz questions the soloistic principle: in this music no soloist takes the focus, everything

is composition and form, expressed in the sound of the ensemble. This group practices jazz as a team sport. In terms of their concept, this ensemble is more related to a clas- sical string quartet than a hard bop combo. Actually solos survive in this music, even in their collective and free form, but they fulfill a different function: the improvisations serve the composition, they are embedded into the arrangements. Not an end in them- selves, they are a means to an end, always referring to the atmosphere, construction and tonality of the respective piece.

Refined arrangements constitute the interior of the pieces. The melodic instruments of the ensemble (tenor saxophone, electric guitar and cello) all sound in the middle register. Therefore it’s up to the arrangements to bring diversity into the playing by employing the instruments wisely. Inventive combinations of instruments display surprising tone colours.

The musicians draw on the abundant treasure of their musical experience: rock sounds, jazz feeling, popular music, free improvisation as well as classical composition – eve- rything brews together, soundly and organically fermenting into an idiosyncratic style synthesis.

Daniel Erdmann (born 1973) plays his tenor saxophone in multifarious manners but al- ways with his singular artistic identity. Sometimes he’s blasting the hot breath of a young Archie Shepp - then again with the invention and perfectly tailored phrasing of a Stan Getz, or Ben Webster’s tender breathiness. Cellist Vincent Courtois (born 1968) is as agile in changing from bow to pizzicato as he is in swapping bassline for melody. Frank Möbus (born 1966) feeds his guitar through an arsenal of effects, generating spherical tones or howling in rock style. Co-leader Samuel Rohrer (born 1977) contributesseveral highly inventive compositions to the band repertoire. He treats his drums as far more than a rhythm instrument. This melodic drum playing exploits the range of dynamic possibilities, blends in elastically and is always exactly to the point.

Looking for reference points in jazz history, one is reminded of those impressionists of sound who first began painting with tone colours, and had such a strong feel for compo- sition and arrangement: Duke Ellington, Miles Davis with Gil Evans, Jimmy Giuffre too – musicians who for a time played jazz in a deliberately restrained way.

That’s where the Erdmann-Rohrer quartet ties in. Their jazz seems to be damped down, held in check, all moods, shades and nuances – but every now and then revealing some rippling muscle. A passage of cool jazz will snarl into a dirty rock riff a couple of bars later, then tumble into a collective improvisation or an intricate unison passage. Nothing gets out of hand, everything is dished out in correct portions.

Apart from self-restraint, a sense of proportion is an essential attribute of this mysteri- ous jazz. The short duration of the pieces suits the understated nature of the album perfectly. Not designed as epics (the longest is 8 minutes), they are highly compact oeuvres, or miniatures that might just evaporate after 50 seconds. Ideas are not spun out at length but just subtly hinted at. Further elaboration is left to the listener’s fantasy. And for this the Erdmann-Rohrer quartet offers abundant stimulation.

Christoph Wagner / Translation: Sigrun Andree